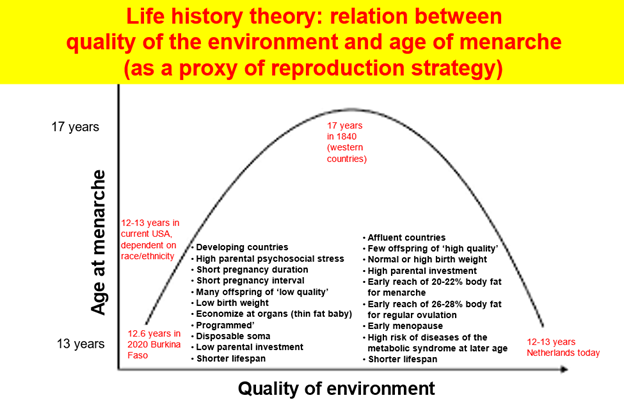

Meisjes worden steeds jonger voor de eerst keer ongesteld. Waarom daalt de leeftijd van deze ‘menarche’? Het antwoord is gelegen in de welvaart. Deze lijkt ons te programmeren voor een korter leven.

Tussen diersoorten gaat een korte levensduur samen met hoog levenstempo. Dit uit zich in een klein lichaam, hoog energieverbruik, snelle hartslag, snelle ontwikkeling tot volwassene en een snelle veroudering. De onderliggende natuurwet vind je in voordelen voor de reproductie. Dus het nageslacht, want daar gaat het in de evolutie immers om. Een hoog levenstempo gaat daarom gepaard met een vroege seksuele rijping, korte zwangerschapsduur en veel nageslacht. Hoe meer nageslacht, hoe groter de kans op overleving van de soort. Denk hierbij aan muizen en konijnen. Een laag levenstempo daarentegen gaat samen met late seksuele rijping, lange zwangerschapsduur en weinig nageslacht. ‘Less is dan dus more’: de kwaliteit van het nageslacht is daarbij belangrijker dan de kwantiteit. Denk hierbij aan olifanten, maar ook aan mensen (1-4).

Verschillen in levenstempo, voortplantingsstrategie en levensduur, gelden niet alleen tussen de diersoorten maar ook voor individuen binnen een enkele soort, zoals de mens (2-5). De omstandigheden in de baarmoeder ‘programmeren’ het kind voor een succesvolle reproductie als volwassene (6-8). Optimale omstandigheden (voldoende goede voeding, geen stress bij de moeder), programmeren ons voor een lager tempo van leven, waarbij meisjes laat ongesteld worden en dus ook laat kinderen krijgen. Als de omstandigheden in de baarmoeder ongunstig zijn, wordt de voedingsbodem gelegd voor een ‘hoger tempo van leven’ (1-5). Het kind wordt dan als het ware ‘afgeraffeld’. Het wordt vroeger geboren, is kleiner en er is bezuinigd op nagenoeg alle organen, behalve de hersenen. Dit fenomeen gaat vaak samen met een vroege ongesteldheid en wordt bijvoorbeeld gezien in het zuiden van de VS en India (6-8,34).

Lichaamsvetgehalte waarbij menstruatie kan starten, wordt steeds sneller bereikt

In 1840 lag de gemiddelde leeftijd voor de menarche in westerse landen op ongeveer 17 jaar, terwijl dat nu rond de 12-13 jaar ligt (21,39). Van 1940 naar 2000 daalde ook in de lage- en middel-inkomen landen de leeftijd van de menarche van 14 naar 13 jaar (22,23). In Nederland ging het van 1955 tot 2009 van 13,66 naar 13,15 jaar. Bij Turkse en Marokkaanse meisjes was de leeftijd van de menarche nog lager: rond de 12,55 jaar (24).

De recente dalingen hebben vooral te maken met de sterke toename van overgewicht (25). Chimpansees in het wild beginnen te menstrueren op 10,4 jarige leeftijd en voor hun collega’s, die genieten van een gezapig leventje in gevangenschap, is dat 8,2 jaar (26). Met kunstmest doe je overigens hetzelfde bij planten. Ze groeien snel, bloeien vroeg met een hoge opbrengst, leven kort en de kwaliteit laat te wensen over (29a,29b). Er is ruim bewijs dat een vroege puberteit geassocieerd is aan een overvloedige voeding van het jonge kind (6-8). Dit hangt ook samen met een grotere lichaamslengte en ook dat relateert aan een vroegere menarche (18,27). De menstruatie kan pas starten als meisjes een lichaamsvetgehalte bereiken van ongeveer 20-22 procent. Deze grens wordt tegenwoordig steeds sneller bereikt (21,28,29).

Wat betekent dit nu voor de gezondheid? Vast staat dat de huidige vroege menarche het risico verhoogt op een vroege menopauze, overgewicht, borst-, baarmoeder- en eierstokkanker, metabool syndroom, diabetes, hart- en vaatziekten en psychosociale problemen, waaronder depressie (21,24,30-34). Zowel een vroege menarche als een vroege menopauze zijn gelinkt aan meer vet in het onderlichaam (35) en een kortere levensduur (36,37).

Hoe eerder een meisje ongesteld is, hoe langer het duurt voordat de cyclus regelmatig wordt. Een vroege menarche gaat dus niet automatisch gepaard met een verhoogde kans op een eerste zwangerschap. Voor een regelmatige cyclus is een lichaamsvetgehalte nodig van zo’n 26-28 procent (39).

Het is de vraag of er een ‘optimale’ menarche leeftijd is voor mensen. Aangezien de meeste mensen lang gezond willen leven, lijkt het verstandig om van meet af aan te focussen op kwaliteit van leven en daarbij hoort een late menarche.

1. Johnson AA, Shokhirev MN, Shoshitaishvili B. Revamping the evolutionary theories of aging. Ageing Res Rev. 2019 Nov;55:100947. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2019.100947. Epub 2019 Aug 23. PMID: 31449890.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31449890

2. Boudoulas KD, Borer JS, Boudoulas H. Heart Rate, Life Expectancy and the Cardiovascular System: Therapeutic Considerations. Cardiology. 2015;132(4):199-212. doi: 10.1159/000435947. Epub 2015 Aug 15. PMID: 26305771.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26305771

3. Yuan R, Hascup E, Hascup K, Bartke A. Relationships among Development, Growth, Body Size, Reproduction, Aging, and Longevity – Trade-Offs and Pace-Of-Life. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2023 Nov;88(11):1692-1703. doi: 10.1134/S0006297923110020. PMID: 38105191; PMCID: PMC10792675.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38105191

3a. Coall DA, Chisholm JS. Evolutionary perspectives on pregnancy: maternal age at menarche and infant birth weight. Soc Sci Med. 2003 Nov;57(10):1771-81. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00022-4. PMID: 14499504.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14499504

3b. Chisholm JS, Burbank VK. Evolution and inequality. Int J Epidemiol. 2001 Apr;30(2):206-11. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.2.206. PMID: 11369714.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11369714

3c. WomanStats database. Latest data for MAA)-DATA-1, accessed 01 August 2024

https://www.womanstats.org/new/data/variable/maao-data-1

4. Kevinbinz. The Pace of Life, 18 augustus 2022, accessed 27 July 2024

5. Mishra GD, Cooper R, Tom SE, Kuh D. Early life circumstances and their impact on menarche and menopause. Womens Health (Lond). 2009 Mar;5(2):175-90. doi: 10.2217/17455057.5.2.175. PMID: 19245355; PMCID: PMC3287288.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19245355

6. Gluckman PD, Hanson MA. Evolution, development and timing of puberty. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Jan-Feb;17(1):7-12. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2005.11.006. Epub 2005 Nov 28. PMID: 16311040.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16311040

7. Gluckman PD, Hanson MA. Changing times: the evolution of puberty. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006 Jul 25;254-255:26-31. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.04.005. Epub 2006 May 18. PMID: 16713071.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16713071

8. Gluckman, P., Beedle, A., Buklijas, T., Low, F., & Hanson, M. (2016). Principles of evolutionary medicine. Oxford University Press.

9. Yajnik C. Interactions of perturbations in intrauterine growth and growth during childhood on the risk of adult-onset disease. Proc Nutr Soc. 2000 May;59(2):257-65. doi: 10.1017/s0029665100000288. PMID: 10946794.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10946794

10. Yajnik CS, Lubree HG, Rege SS, Naik SS, Deshpande JA, Deshpande SS, Joglekar CV, Yudkin JS. Adiposity and hyperinsulinemia in Indians are present at birth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002 Dec;87(12):5575-80. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020434. PMID: 12466355.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12466355

11. Yajnik CS. Obesity epidemic in India: intrauterine origins? Proc Nutr Soc. 2004 Aug;63(3):387-96. doi: 10.1079/pns2004365. PMID: 15373948.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15373948

12. Modi N, Thomas EL, Uthaya SN, Umranikar S, Bell JD, Yajnik C. Whole body magnetic resonance imaging of healthy newborn infants demonstrates increased central adiposity in Asian Indians. Pediatr Res. 2009 May;65(5):584-7. doi: 10.1203/pdr.0b013e31819d98be. PMID: 19190541.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19190541

13. Chew LC, Verma RP. Fetal Growth Restriction. [Updated 2023 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562268

14. Chumlea WC, Schubert CM, Roche AF, Kulin HE, Lee PA, Himes JH, Sun SS. Age at menarche and racial comparisons in US girls. Pediatrics. 2003 Jan;111(1):110-3. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.1.110. PMID: 12509562.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12509562

15. Hayes P, Tan TX. Timing of menarche in girls adopted from China: a cohort study. Child Care Health Dev. 2016 Nov;42(6):859-862. doi: 10.1111/cch.12393. Epub 2016 Aug 21. PMID: 27545904.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27545904

16. Street ME, Ponzi D, Renati R, Petraroli M, D’Alvano T, Lattanzi C, Ferrari V, Rollo D, Stagi S. Precocious puberty under stressful conditions: new understanding and insights from the lessons learnt from international adoptions and the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023 May 2;14:1149417. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1149417. PMID: 37201098; PMCID: PMC10187034.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37201098

17. Teilmann G, Pedersen CB, Skakkebaek NE, Jensen TK. Increased risk of precocious puberty in internationally adopted children in Denmark. Pediatrics. 2006 Aug;118(2):e391-9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2939. PMID: 16882780.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16882780

18. Onland-Moret NC, Peeters PH, van Gils CH, Clavel-Chapelon F, Key T, Tjønneland A, Trichopoulou A, Kaaks R, Manjer J, Panico S, Palli D, Tehard B, Stoikidou M, Bueno-De-Mesquita HB, Boeing H, Overvad K, Lenner P, Quirós JR, Chirlaque MD, Miller AB, Khaw KT, Riboli E. Age at menarche in relation to adult height: the EPIC study. Am J Epidemiol. 2005 Oct 1;162(7):623-32. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi260. Epub 2005 Aug 17. PMID: 16107566.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16107566

19. Wang Z, Asokan G, Onnela JP, Baird DD, Jukic AMZ, Wilcox AJ, Curry CL, Fischer-Colbrie T, Williams MA, Hauser R, Coull BA, Mahalingaiah S. Menarche and Time to Cycle Regularity Among Individuals Born Between 1950 and 2005 in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 May 1;7(5):e2412854. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.12854. PMID: 38809557; PMCID: PMC11137638.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38809557

20. Nwaz A. New study details potential long-term health risks as American girls reach puberty earlier PBS news 31 mei 2024 6:25 PM EDT, accessed 30 July 2024

21. Lee HS. Why should we be concerned about early menarche? Clin Exp Pediatr. 2021 Jan;64(1):26-27. doi: 10.3345/cep.2020.00521. Epub 2020 Jul 13. PMID: 32683812; PMCID: PMC7806408.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32683812

22. Leone T, Brown LJ. Timing and determinants of age at menarche in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2020 Dec;5(12):e003689. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003689. PMID: 33298469; PMCID: PMC7733094.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33298469

23. Meher T, Sahoo H. Secular trend in age at menarche among Indian women. Sci Rep. 2024 Mar 5;14(1):5398. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-55657-7. PMID: 38443461; PMCID: PMC10914750.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38443461

24. Talma H, Schönbeck Y, van Dommelen P, Bakker B, van Buuren S, Hirasing RA. Trends in menarcheal age between 1955 and 2009 in the Netherlands. PLoS One. 2013 Apr 8;8(4):e60056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060056. PMID: 23579990; PMCID: PMC3620272.

25. Barros BS, Kuschnir MCMC, Bloch KV, Silva TLND. ERICA: age at menarche and its association with nutritional status. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2019 Jan-Feb;95(1):106-111. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2017.12.004. Epub 2018 Jan 18. PMID: 29352861.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29352861

26. Atsalis S, Videan E. Reproductive aging in captive and wild common chimpanzees: factors influencing the rate of follicular depletion. Am J Primatol. 2009 Apr;71(4):271-82. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20650. PMID: 19067363.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19067363

27. Bogin B. Adolescence in evolutionary perspective. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 1994 Dec;406:29-35; discussion 36. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb13418.x. PMID: 7734808.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7734808

28. Huang L, Hou JW, Fan HY, Tsai MC, Yang C, Hsu JB, Chen YC. Critical body fat percentage required for puberty onset: the Taiwan Pubertal Longitudinal Study. J Endocrinol Invest. 2023 Jun;46(6):1177-1185. doi: 10.1007/s40618-022-01970-9. Epub 2022 Nov 27. PMID: 36436189; PMCID: PMC9702699.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36436189

29. Baker ER. Body weight and the initiation of puberty. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1985 Sep;28(3):573-9. doi: 10.1097/00003081-198528030-00013. PMID: 4053451.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4053451

29a. Lundgren MR, Des Marais DL. Life History Variation as a Model for Understanding Trade-Offs in Plant-Environment Interactions. Curr Biol. 2020 Feb 24;30(4):R180-R189. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.01.003. PMID: 32097648.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32097648

29b. Gremer JR. Looking to the past to understand the future: linking evolutionary modes of response with functional and life history traits in variable environments. New Phytol. 2023 Feb;237(3):751-757. doi: 10.1111/nph.18605. Epub 2022 Dec 5. PMID: 36349401.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36349401

30. Bjelland EK, Hofvind S, Byberg L, Eskild A. The relation of age at menarche with age at natural menopause: a population study of 336 788 women in Norway. Hum Reprod. 2018 Jun 1;33(6):1149-1157. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey078. PMID: 29635353; PMCID: PMC5972645.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5972645

31. Mishra GD, Pandeya N, Dobson AJ, Chung HF, Anderson D, Kuh D, Sandin S, Giles GG, Bruinsma F, Hayashi K, Lee JS, Mizunuma H, Cade JE, Burley V, Greenwood DC, Goodman A, Simonsen MK, Adami HO, Demakakos P, Weiderpass E. Early menarche, nulliparity and the risk for premature and early natural menopause. Hum Reprod. 2017 Mar 1;32(3):679-686. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew350. PMID: 28119483; PMCID: PMC5850221.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5850221

32. Thomas L. Early Menarche and Long-Term Health: What the Research Says. Accessed 30 July 2024

https://www.news-medical.net/health/Early-Menarche-and-Long-Term-Health-What-the-Research-Says.aspx

33. Yoo JH. Effects of early menarche on physical and psychosocial health problems in adolescent girls and adult women. Korean J Pediatr. 2016 Sep;59(9):355-361. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2016.59.9.355. Epub 2016 Sep 21. PMID: 27721839; PMCID: PMC5052133.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27721839

34. Adair LS. Size at birth predicts age at menarche. Pediatrics. 2001 Apr;107(4):E59. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.4.e59. PMID: 11335780.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11335780

35. Banack HR, Cook CE, Grandi SM, Scime NV, Andary R, Follis S, Allison M, Manson JE, Jung SY, Wild RA, Farland LV, Shadyab AH, Bea JW, Odegaard AO. The association between reproductive history and abdominal adipose tissue among postmenopausal women: results from the Women’s Health Initiative. Hum Reprod. 2024 Jun 18:deae118. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deae118. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 38890130.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38890130

36. Shadyab AH, Macera CA, Shaffer RA, Jain S, Gallo LC, Gass ML, Waring ME, Stefanick ML, LaCroix AZ. Ages at menarche and menopause and reproductive lifespan as predictors of exceptional longevity in women: the Women’s Health Initiative. Menopause. 2017 Jan;24(1):35-44. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000710. PMID: 27465713; PMCID: PMC5177476.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27465713

37. Frellick M. Longevity Linked to Late Menarche, Late Menopause Medscape 2 augustus 2016, accessed 30 July 2024

https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/866931

38. Martinez GM. Trends and Patterns in Menarche in the United States: 1995 through 2013-2017. Natl Health Stat Report. 2020 Sep;(146):1-12. PMID: 33054923.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33054923

39. Frisch RE. The right weight: body fat, menarche and ovulation. Baillieres Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 1990 Sep;4(3):419-39. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3552(05)80302-5. PMID: 2282736.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2282736

Beeld: OpenAI

MMV maakt wekelijks een selectie uit het nieuws over voeding en leefstijl in relatie tot kanker en andere medische condities.

Inschrijven nieuwsbrief